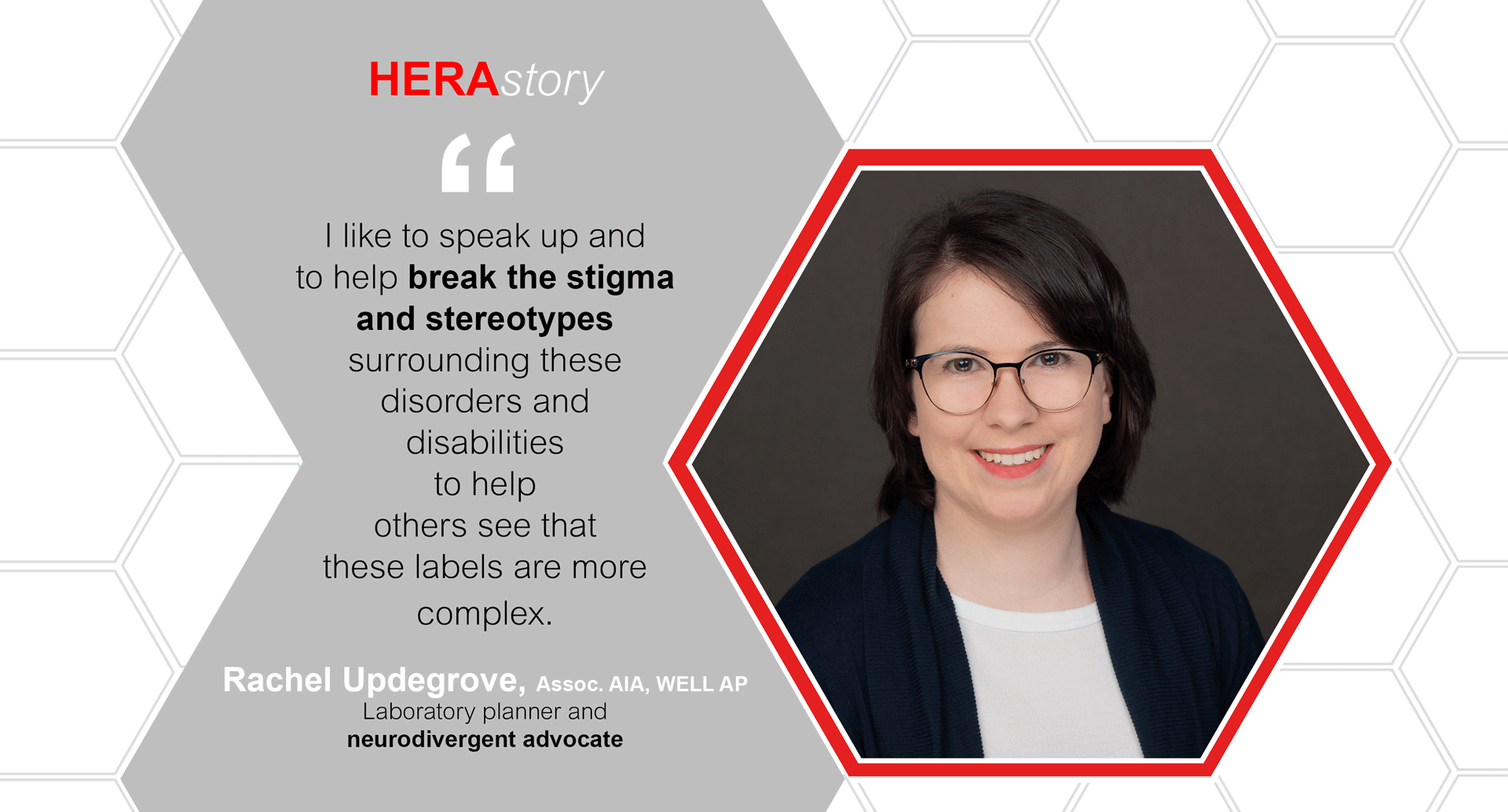

Q&A with Laboratory Planner Rachel Updegrove, Assoc. AIA, WELL AP.

You’ve been an outspoken advocate for the neurodivergent community. What is your connection?

From my lived experience. I am autistic and have ADHD and OCD. But until I was diagnosed, I didn’t know much about any of these things. I like to speak up to help break the stigma and stereotypes surrounding these disorders and disabilities, to help others see that these labels are more complex. I was first diagnosed at the end of my freshman year of college with OCD, which is a time of change of environment and routine that sparked me talking to professionals. Then again at the end of college, adjusting to real world and working full time was difficult because of the change in routine. It was at that time I sought and autism and ADHD diagnosis, but even that was no easy feat. I was almost misdiagnosed with borderline personality disorder, which is not uncommon for women who often get diagnosed later in life, and autistic women present differently than autistic men. Much of the autism diagnosis criteria are based on young boys. Being an adult female made the diagnosis process much harder.

You’ve spoken quite a lot over the past several years at symposiums or conferences about neurodiversity and design. Are there key takeaways you always try to impart?

Moving away from stereotypes. Because I often feel like an “other,” even in the neurodivergent community, I always try to play devil’s advocate. For example, one stereotype is that many believe neurodivergent people, especially autistic people or those with sensory processing disorder, need soothing environments and low simulations. But that’s not always the case. The reality is there’s a big range of needs, and those range of needs change on the daily, based on the physical, social and emotional environment. For example, my best friend (who is also neurodivergent) hates bright light, but I love it. In college she’d sit in the dark living room with her computer screen glowing while I’d sit in my bedroom with all the lights on and position myself so that I could still see her through my door opening. We can’t design spaces that isolate people – like creating one space for high stimulation and one space for low stimulation. We must find creative ways of designing so that all preferences can exist in the same space together.

Where have you been able to positively affect an outcome in a project by providing a different voice or perspective?

I’ve been involved with HERA’s post occupancy evaluations, and seeing the feedback makes me realize how important communication is in design. Half the world doesn’t understand floorplans. They’re abstract. Color coding or showing product images are two strategies to reduce miscommunication.

Interestingly, laboratory spaces are probably comforting to the neurodivergent community because there is some predictability. The pattern making of a lab module helps with finding and navigating a new space. We love patterns.

You’re now teaching at Thomas Jefferson University (your alma mater). How has that experience been?

I love it! I absolutely love it! I teach two mornings a week in the space where I was a student. That psychological connection makes me go back to “school” mode, and find I am sometimes more productive working from there after class. Teaching has also been helpful because it’s given me an opportunity to practice communicating in a new way with a different audience. For example, a few weeks ago I was talking with my students about how a lot of the work I do at HERA is equipment planning. When I mentioned that there is a lot of coordination with MEP, my students (who are sophomores) asked, “What is MEP?” It was a great question! They don’t know what they don’t know.

And how do you use that with HERA clients?

I’ve found it’s transferable to communicating with coworkers or communicating with clients. One design challenge we see sometimes is that people don’t know our process. For students, they might be doing a project and not understand how it’s related to architecture. I give them little nuggets of how the analysis and critical thinking they’re doing could transform into architecture. Similarly, when we’re working with clients, they don’t necessarily know our design process even if they’ve been shown it at the beginning of a project. You have to remind them we’re on a journey and everything we’re doing is baby steps. What the neurodivergent community can teach us is that everyone can benefit from preparing people ahead of a meeting so they know what they’re getting into before they are getting into it.